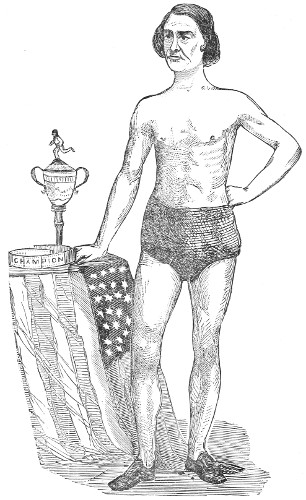

GEORGE SEWARD, THE AMERICAN WONDER, who ran 100 yards in 9¼secs.

Practical Training (Walking and Running)

by Ed James

GEORGE SEWARD, THE AMERICAN WONDER,

who ran 100 yards in 9¼secs.

Preface

Notwithstanding that so many books have been written on Physical Culture, there still remained a large field to be covered—hence the publication of the present volume. Great care having been taken in its compilation, we feel confident that the work will be in every sense of the word practical; so that those who desire may follow whatever their fancy prefers in athletic sports, in a creditable manner. In our opinion, the general usefulness of the book could in no way be improved upon.

Contents

Introductory

Advice to Trainers

Training for Pedestrianism

Sleep

Clothing

Time and Duration of Training for Running

Sprint Running

Quarter and Half Mile Running

One Mile Running and upwards

Hurdle Racing

Hints In, Before, and After the Race

Training Practice, Fair Walking, etc.

Introduction

Pedestrianism, from its being the basis and principal agent in securing a thorough and perfect training to all who may have, from choice or necessity, to undergo a great amount of physical exertion, may be considered the chief feature in the preparation of men for all contests in which great strength, speed, and wind may be required. From this point of view the science of walking will be treated in the present work; for whether a man may have entered in an engagement to run, walk, jump, swim, row, or box, no training can be thoroughly accomplished until the athlete has undergone a certain amount of exercise on foot, and reduced his superfluous weight to such an extent that he can follow up his peculiar forte with fair chance of improvement, or at least so that he may not have to stop short from sheer want of wind or strength.

Pedestrianism, which has before been stated to be more or less indispensable to the man undergoing preparation, from its healthful and beneficial effect upon the human frame, is of most vital importance in keeping the required equable balance which should exist in every constitution, whether robust or otherwise. Good training is as requisite to any man who wishes to excel, as it is to the thoroughbred race-horse. A man who is fleshy and obese might as well attempt to compete with a well-trained man as the race-horse that has been fed for a prize-show to again enter the lists with his highly-prepared and well-trained contemporaries. A man may be endowed with every requisite in health, strength, muscle, length, courage, bone, and all other qualifications; but if untrained, these qualifications are of no value, as, in every instance, a man or horse, well-trained, of much inferior endowments, has always under the circumstances proved the victor. Good condition, which is the term used by trainers to indicate the perfect state of physical power to which the athlete has arrived, is one of the greatest safeguards to his health; as, in many instances, severe and long-continued exertion when unprepared has had an injurious and continuous effect on the constitution, and, in some few but fortunately almost isolated cases, produced almost instant death. These few words are not alone intended for the man who has to compete, but for a great portion of mankind, who go through the regular routine of life day after day, their business being sometimes performed with apathy, and the remainder of their time passed in excessive smoking, eating, drinking, sleeping, sitting, or any small pet vice to which they may be addicted. That such a man can undergo the same process of training as the professional who has an engagement to perform some arduous task against time or a fleet antagonist, we do not ask or expect—his occupation would not allow the same time; but the assertion that he would perform his allotted duties with more pleasure to himself and more satisfaction to all concerned if he were to submit to undergo a partial training, is a truth that ought to be tested by all who have any regard for continued good health. Were this system carried out to even a small extent, the physician would have cause to lament the decline of his practice, and the advertising quack become a nonentity. As a proof how necessary training is considered by the professional, it is only requisite to ask any pedestrian of note for his candid opinion to satisfy the most incredulous. The higher in the pedestrian grade the man may be to whom the question may be put the better, in consequence of his having gone through the whole performance, from novicehood upwards; and, in every instance, it will be found that more than one of his defeats will be attributed to want of condition (proper training) arising from neglect of work or other causes, such as carelessness in diet, want of practice, and, in some instances, from the neglect of the precepts attempted to be inculcated by his trainer. Most of the above mistakes have arisen from overweening confidence in his own powers, or from underrating his adversaries' abilities. However willing and thoughtful he may have been, these contretemps have almost invariably been the fate of all our leading athletes, not only in the pedestrian circle, but in the ring, on the water, and in all sports in which a great lead has ever been taken by man. He will inform the querist that he will require from a month to two months for his preparation, and if he has been out of practice for some time, even more—thus showing to the dullest intellect the requisite time and attention needed; for if a man who has shone pre-eminent in the sphere he has chosen for his exertions, and has had the benefit of previous trainings, must again undergo the same ordeal as heretofore, a man totally untrained must at least require the same preparation, as well as a greater amount of practice, to fully develop his particular forte as a pedestrian. To sum up in a few words, training is a complete system of diet and exercise duly carried out and strenuously adhered to. From the mode of life which almost all lead, the health becomes impaired, and the only remedy will be discovered by him who follows the principle of training in some form or other, the more simple the better. That the same system of training will suit all constitutions, it would be absurd folly to advance; or that the same amount of work and strictness of diet is requisite for a man about to run a race of one hundred and twenty yards, as for a struggle of an hour's duration, would be equally preposterous. Nevertheless, the groundwork of training arises from the benefits derived from regular diet and steady exercise. Training will bring out all the hitherto latent powers of the athlete, raising the man who has previously been considered almost a nonentity into public notice, the one of mediocre calibre into the first rank, and thoroughly develop the excellencies, etc., of the first-class proficient to an extent that will not only surprise himself, but his associates and long-tried friends and backers.

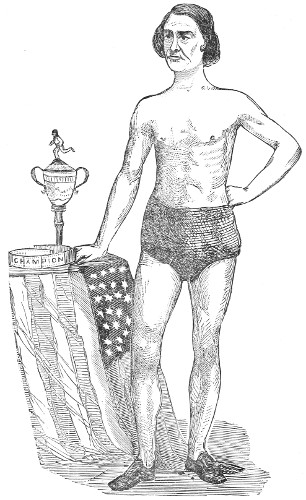

CHARLES ROWELL, Champion Long-distance Pedestrian of the World.

WILLIAM GALE, who walked 4,000 quarter miles in 4,000 consecutive 10 minutes

Advice To Trainers

Training is the process of getting a man who has to perform any muscular feat from a state of obesity and almost total incapability into a perfect state of health, which is shown by the great increase of strength, activity, wind, and power to continue great exertion and pace to the extent of his endowments. It is this acquired power which enables the pedestrian to persevere in his arduous task, apparently in despite of nature, which, but for his thorough preparation, would have long before been utterly prostrate. So much is depending on, and so many results accruing to the efficiency of the trainer, that a few words of friendly advice to that official will not be out of place; for although the veteran has learned the precepts given below by heart, yet there is always a beginning to all occupations. As a rule, a great pedestrian is not qualified at the outset of his career as a trainer to undertake the care of most men, in consequence of there being a leaven of the remembrance of the manner in which he went through his work, etc., which will in most instances render him less tolerant than is requisite to the man of mediocre talent. Another difficulty is to find one with sufficient education and forethought to be able to study the different constitutions of the men under his rule. The above are only a few of the objections; but all are of consequence, so much depending upon the treatment of the man independent of his daily routine of exercise and diet. The man who goes first into training is like an unbroken colt, and requires as much delicate treatment. The temper of the biped ought to be studied as carefully as that of the quadruped, so that his mind can be carefully prepared for his arduous situation, which is one of abstinence, and in some cases total deprivation, which always tries the patience and frequently the temper of the competitor, who in these cases should be encouraged by word and example, showing that the inconveniences he is undergoing are but the preliminary steps to the attainment of that health, strength, and elasticity of muscle which have caused so many before him to accomplish almost apparent impossibilities. Such a trainer is worth a hundred of those who have no judgment in the regulation of the work which a man may take without in any way making him anxious to shun his duty or to turn sullen. Let the trainer bear in mind and always remember that a fit of ill-temper is as injurious to the man in training as any other excess. In many instances, from a supposed well-founded cause of complaint, a continued civil war has arisen in the cabinet, which has not been quelled, perhaps, until the dissension has had a very serious effect in destroying the pedestrian's confidence in his trainer's capabilities and temper, as well as throwing back the trained man most materially in his advance towards condition. Nevertheless, the mentor should be firm in his manner, intelligible in his explanations, and by no means bigoted in his favorite notions respecting the use of any particular medicine or “nostrum” which he may think may be requisite to the welfare of his man. The trainer, of course, is known or supposed to be of sterling integrity, and having the welfare of his man as his first aim; and on this in a great measure depends the monetary interests of the man and his backers. We are sorry to have to mention that such a man is requisite as a trainer, but consider it necessary to mention it, as, if the trainer is not honest, and has not his heart in the well-doing of his man, all the pains taken by the pedestrian would be nullified and rendered of no avail. The trainer must be vigilant night and day, never leave his man, and must act according to his preaching, and be as abstemious, or nearly so, as his man, whom it is his duty to encourage in improvement, to cheer when despondent, and to check if there are at any time symptoms of a break-out from the rules laid down—but at all times he must, by anecdote, etc., keep the mind of his man amused, so that he may not brood over the privations he is undergoing. Let the trainer not forget that cleanliness is one of the first rules to be attended to, and that the bath can hardly hurt his man in any season if only due precautions be observed, always bearing in mind that it is a preventive instead of a provocative to colds, catarrhs, and the long list of ills attendant upon a sudden chill. The duration of the bath is, of course, to be limited, and a brisk rubbing with coarse linen cloths until the surface is in a glow will always be found sufficient to insure perfect safety from danger. Of course, the amount of medicine required by any man will depend upon his constitution as well as the lowness of his nervous system, in some cases there being no occasion to administer even a purgative. But these are the times when the skill of the trainer is brought into requisition, and if he knows his business he will in these instances give his man stimulating and generous diet, until he is enabled to undergo the necessary privations to get him into a proper state to be called upon to work to get into condition. In no instance ought he to allow his man to sweat during the days on which he has taken a purgative, as in many instances men have been thrown back in their preparation, or, as it is professionally termed, “trained off.” The best test when all the superfluous flesh has been trained off by sweating, by long walks or runs, as the case may be, is taken from the fairness and brightness of the skin, which is a certain criterion of good health. The quickness with which perspiration is dried on rubbing with towels, sufficient leanness and hardness of the muscles, is also the right test that reducing has been carried to the proper extent.

Training For Pedestrianism

There being so many classes of individuals who may derive benefit from training, each of whom have different modes of living, and whose particular line of excellences are as different from each other as light from dark, it must be patent to all that the same system carried out to the letter would not have the same beneficial effect on all, the more especially in the dietary system, which, in almost every case, would require some change, as no two men have ever scarcely been found to thrive equally well on a stereotyped rule. The pedestrian alone comprises a class by itself, which is subdivided into as many different ramifications as there are other sports and professions that require severe training; therefore, as pedestrianism is the groundwork of all training and all excellence in athletic games, it is the intention to give the hints requisite for the man who is matched to get himself sufficiently well in bodily health and bodily power to undergo his practice with credit to himself and trainer, and justice to his backers. In all engagements for large amounts there is almost invariably a trainer engaged to attend to the man who is matched, who is supposed to thoroughly understand his business; therefore these few words are not intended for the guidance of those in the said position, but for those who may wish to contend for superiority, for honor, or small profit. The same amount of work and strict regimen is not requisite for the sharp burst of a hundred yards or so, that it is imperative on the trained man to undergo if in preparation for the more arduous struggle of a mile's duration; but, as stated before, the theory of the practice is the same. Westhall found that the more work he had taken at the commencement of his training, after having undergone the requisite medical attention, the easier and better his fast trials were accomplished when hard work was put on one side and daily practice took place against a watch. Yet he, in pedestrian language, could race up to a hundred and sixty yards, but not finish two hundred properly—could run three hundred yards and a quarter of a mile, but yet not be equally good at three hundred and fifty. The same was found to be the case at the different distances up to a mile, which is the farthest distance he had practiced. The first and primary aim ought to be the endeavor to prepare the body by gentle purgative medicines, so as to cleanse the stomach, bowels, and tissues from all extraneous matter, which might interfere with his ability to undergo the extra exertion it is his lot to take before he is in a fit state to struggle through any arduous task with a good chance of success. The number of purgatives recommended by trainers are legion, but the simpler will always be found the best. A couple of anti-bilious pills at night, and salts and senna in the morning, has answered every purpose. It is reasonable, however, to suppose that anyone who has arrived at sufficient years to compete in a pedestrian contest has found out the proper remedies for his particular internal complaints. The internal portion of the man's frame, therefore, being in a healthy condition, the time has arrived when the athlete may commence his training in proper earnest; and if he be bulky, or of obese habit, he has no light task before him. If he has to train for a long-distance match, the preparation will be almost similar, whether for walking or running. The work to be done depends very much on the time of year. In the summer the man should rise at five in the morning, so that, after having taken his bath, either shower or otherwise, there will have been time for a slow walk of an hour's duration to have been taken before sitting down to breakfast—that is, if the weather be favorable; but if otherwise, a bout at the dumb-bells, or half an hour with a skipping-rope, swinging trapeze, or vaulting-bar, will be found not unfavorable as a good substitute. Many men can do without having any nourishment whatever before going for the morning's walk, but these are exceptions to the rule. Most men who take the hour's walk before breaking their fast feel faint and weak in their work after breakfast, at the commencement of their training, and the blame is laid on the matutinal walk; when, if a new-laid egg had been beaten in a good cup of tea, and taken previous to going out, no symptom of faintness would have been felt, although it is expected some fatigue would be felt from the unwonted exertion. The walk should be taken at such a pace that the skin does not become moist, but have a good healthy glow on the surface, and the man be at once ready for his breakfast at seven o'clock. The breakfast should consist of a good mutton chop or cutlet, from half a pound upwards, according to appetite, with dry bread at least two days old, or dry toast, washed down with a cup or two of good tea (about half a pint in all), with but little and if possible no milk. Some give a glass of old ale with breakfast, but it is at this time of the day too early to introduce any such stimulant. After having rested for a sufficient time to have allowed the process of digestion to have taken place, the time will have arrived for the work to commence which is to reduce the mass of fat which at this time impedes every hurried action of the muscle and blood-vessel. This portion of the training requires great care and thought, for the weight of clothing and distance accomplished at speed must be commensurate with the strength of the pedestrian. At the commencement of the work a sharp walk of a couple of miles out, and a smart run home, is as much as will be advisable to risk. On the safe arrival at the training quarters, no time must be lost in getting rid of the wet clothes, when a thorough rubbing should be administered, after which he should lay between blankets, and be rubbed from time to time until the skin is thoroughly dry. Most of the leading pedestrians of the day now, when they come in from their run, divest themselves of their reeking flannels, and jump under a cold shower-bath, on emerging from which they are thoroughly rubbed down, which at once destroys all feeling of fatigue or lassitude. In a few days the pedestrian will be able to increase his distance to nearly double the first few attempts at a greater pace, and with greater ease to himself. After again dressing, he must always be on the move, and as the feeling of fatigue passes away he will be anxiously waiting for the summons to dinner, which should come about one o'clock, and which should consist of a good plain joint of the best beef or mutton, with stale bread or toast, accompanied by a draught of good sound old ale, the quantity of which, however, must be regulated by the judgment of the trainer. It has been found of late years that extreme strictness in all cases should be put on one side, and a small portion of fresh vegetables allowed, such as fresh greens or potatoes; and, in some instances, good light puddings have been found necessary to be added to the bill of fare when the appetite, from severe work or other causes, has been rendered more delicate than usual.

The continued use of meat and bread, unless the man has a wonderful appetite and constitution, will once, if not more, in almost every man's training, pall upon his palate, when the trainer should at once try the effect of poultry or game, if possible; but, at any rate, not give the trained man an opportunity of strengthening his partial dislike to his previous fare. In cases like these, the only wrong thing is to persevere in the previous diet; for if a man cannot tackle his food with a healthy appetite, how is it possible that he can take his proper share of work? The quantity of ale should not exceed a pint, unless there has been a greater amount of work accomplished in the morning than usual, when a small drink of old ale at noon would be far from wrong policy, and a good refresher to the imbiber. Wine in small quantities is sometimes beneficial, but should not be taken at all when malt liquors are the standard drink. If it is possible to do without wine, the better. The chief thing in diet is to find out what best agrees with the man, and which in most instances will be found to be what he has been most used to previously.

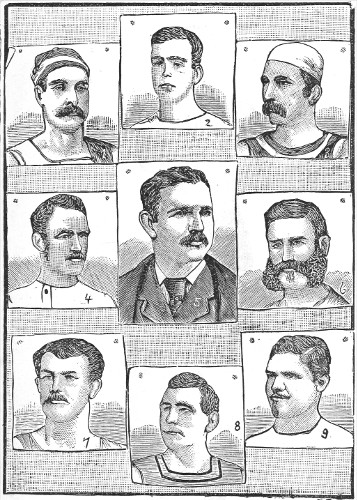

Celebrated Single-Scull Oarsmen

| 1. Chas. E. Courtney. | 2. W. Ross. | 3. Jas. H. Riley. |

| 4. Ed. Trickett. | 5. Ed. Hanlan. | 6. E. C. Laycock. |

| 7. Warren Smith. | 8. J. Higgins. | 9. W. Elliott. |

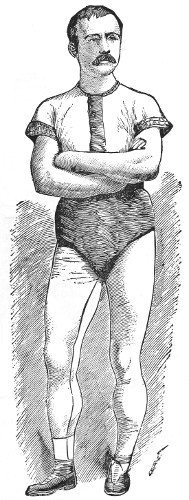

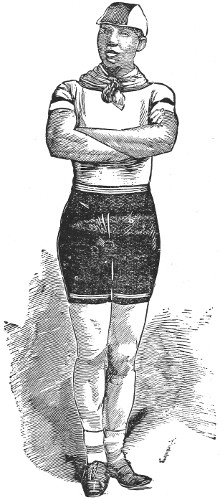

FRANK HART, Second Winner of the O'Leary Champion American Belt

After a thorough rest of an hour's duration, the pedestrian should stroll about for an hour or two, and then, divesting himself of his ordinary attire, don his racing gear and shoes, and practice his distance, or, at any rate, some portion of the same, whether he is training either for running or walking. This portion of the day's work must be regulated by the judgment and advice of the trainer, who of course is the holder of the watch by which the athlete is timed, and is the only person capable of knowing how far towards success the trained man has progressed in his preparation. It is impossible for the pedestrian to judge by his own feelings how he is performing or has performed, in consequence of, perhaps, being stiff from his work, weak from reducing, or jaded from want of rest. The trainer should encourage his man when going through his trial successfully, but stop him when making bad time, if he is assured the tried man is using the proper exertion. The rule of always stopping him when the pedestrian has all his power out, and yet the watch shows the pace is not “up to the mark,” should never be broken; for the man who so struggles, however game he may be, or however well in health, takes more of the steel out of himself than days of careful nursing will restore. If stopped in time, another trial may be attempted on the following day, or, at any rate, the next but one. In a trial for a sprint race, which of course must be run through to know the time, if the day is any way near at hand, suppose a week or ten days off, total rest should be taken the following day until the afternoon, when another trial should take place, when a difference in favor of the pedestrian will in most instances be found to have been accomplished. In Westhall's experience in sprint racing there has been invariably the above successful result. Of course, after the trial a good hand rubbing should be administered, and the work of the day be considered at an end. Tea-time will now have arrived, and the meal should consist of stale bread or toast and tea, as at breakfast, and, if the man has a good appetite, a new-laid egg or two may be added with advantage. In the summer a gentle walk will assist to pass away the time until bed-time, which should be at an early hour. Before getting into bed another good rubbing should be administered, and the man left to his repose, which will in most cases be of the most sound and refreshing character.

Sleep

Of this eight hours is an outside limit, and from six to seven will generally be found sufficient, retiring to rest not later than 11 P. M., and rising from about 6 a. m. to 7.30. A. M., according to circumstances. The bedroom window should always be kept open at top and bottom, slightly in winter and wide in summer. Foul air generated by the human breath is never more hurtful than in a bedroom. Too much clothing should not be placed over the chest whilst sleeping, as by so doing respiration is more labored, and the legs and extremities, not the trunk, require extra covering for purposes of warmth. A mattress should be always used to sleep on, never a feather bed. High pillows and bolsters are very injurious. The natural height to which the head should be raised in sleep is about the thickness of the upper portion of the arm, which constitutes the pillow as designed by nature.

Clothing

Flannel should be worn next the skin throughout the year, but beyond this no restriction is necessary when in mufti. The best attire for running is a pair of thin merino or silk drawers, reaching to the knee and confined round the waist by a broad, elastic band. For the upper part of the body a thin merino or silk Jersey is the best. No covering for the head is usually worn, but, in a race of such long duration as a seven miles walking or ten miles running contest, it is advisable to wear a cap or straw hat if the rays of the sun are very powerful. For running, thin shoes made of French calf, and fitting the foot like a kid glove when laced up, are worn. The sole should be thicker than the heel, and contain four or five spikes, the lacing being continued almost down to the toe. For walking races, the heel should be thicker than the sole, and containing a few sparrow-bill nails, none being required in the toes. Chamois leather socks, just covering the toes, but not reaching above the top of the shoe, are the best adapted for running. Ordinary merino socks, but not thick and heavy like worsted ones, and worn over the chamois leather coverings, are the best for walking, as they prevent the dust and grit raised from the path from getting between the shoe and the foot. Except for sweating purposes, heavy clothing should never be worn in practice, the gait and stride being much impeded thereby. A piece of cork of an elongated, egg shape should be grasped in each hand while walking or running.

Time And Duration Of Training For Running

The foregoing are the foundation rules which constitute training, but of course they require modification according to circumstances, which must be left to the judgment of the pedestrian or the trainer, if he has that necessary auxiliary to getting into good condition. For instance, the man has had too much sweating and forced work, in consequence of which he is getting weak, and, in the professional term, “training off.” This will easily be recognized by the muscles getting flaccid and sunken, with patches of red appearing in different portions of the body, and the man suffering from a continual and unquenchable thirst. These well-known symptoms tell the trainer that rest must be given to the pedestrian, as well as a relaxation from the strict rule of diet. A couple of days' release from hard work will in most cases prove successful in allaying the unwelcome symptoms, and far preferable to flying to purgatives for relief.

The space of time which will be required by a young and healthy man will be from six weeks to a couple of months; but longer than this, if possible, would be preferable—not that it would be really wanted to improve on the mere physical condition of the man, but to enable the pedestrian, when able, to go to any limit as regards exertion, and to have time for practice at his particular length; for, however fit a man may be as regards the proper leanness, if unpractised he would have no chance of success. The principal rules of training, therefore, are regularity, moderate work, and abstinence; the other adjuncts are but the necessary embellishments to the other useful rules. When training for running a long distance—say from four to ten miles—the man should most decidedly practice daily; for the shorter length going the whole distance, and for the longer vary the distance, according to the state of health on the day, as well as whether the weather be fine or otherwise. For a short race of a hundred or two hundred yards, the pedestrian, after the body is in good health, does not require very much severe work, but the distance must be accomplished at top speed at least once daily, and about the same time of the day that the match will take place, if possible. The same rules, with comparatively more work, will apply up to 440 yards—a quarter of a mile—after which distance more work becomes necessary.

Sprint Running

Let the novice, some five weeks or so before the day of his race, begin his practice by a steady run, three or four times a day, of a quarter of a mile or so; so gently at first as to produce no stiffness of the muscles when the temperature produced by the exercise has subsided, and the circulation has recovered its usual condition. When the novice has got his legs into moderate good fettle, so that they could stand a little sharp work, he might quicken up for about 50 yards in each of his quarter spins; and as he finds these spins can be accomplished without the slightest strain on any muscle, the long distances may be condensed into two a day, and two sprints of his distance at about a fifth longer time than he would take in the race. By this means the muscles get worked up by degrees to bear the necessary strain required.

As he finds his muscles become hard and flexible, he should lessen the length of his spins until they are of the same length as in the race. This point will be arrived at some nine days or so before the day, and in these nine days all his energies must be devoted to practicing starts and getting quickly into stride. As the day approaches, let him obtain the services of some sprint runner to use as a trial horse; and the best way of turning his trial horse to account is by making him start slowly some 10 yards in the rear, and, as he passes the novice, who is ready at the scratch, let him quicken up into racing pace for about 50 yards. By this means the novice is encouraged to get off quickly, and a surer line can be taken as to improvement in starting than if the trial and himself started on even terms. Again, the tendency of all young runners to watch their adversary at the start is counteracted, the opponent in this way being in advance, with a straight course only left open for the novice to the goal. So many sprinters, from standing in a wrong position at the scratch, or from taking a longer stride with one leg than the other, jostle or run across their opponent in the spin, thereby either losing their own chance of success or depriving others of it. A bad beginning makes a bad end, and nothing is so detrimental to a sprinter as a bad start. He may get shut out, he loses his stride, or perhaps get spiked by the man who has crossed him; and when he does get into proper swing, he is too far behind to be able to make up what was lost at the beginning. Avoid walking long distances; they rather tend to stiffen the muscles and make them slow. Never miss your race; if you can only get one spin daily, make the most of it. Always run in form—that is to say, as you would in the race, on your toes, with an easy, springing action of the thighs. In the race keep your eyes well on the tape, and never lessen your pace when in front, or let misgivings disturb you when behind; your opponent may have the pace of you and not be able to stay. It is better to be a good second than nowhere. Every race you engage in will increase your experience and give you confidence for the next time. Good time for 100 yards ranges from 11 seconds to 10¼, according to the ground, &c. The top speed is seldom obtained until 40 yards are covered. A good sprinter will generally beat two others in 200 yards, each to run 100 yards with him on end. For sprinting, wind is not such a desideratum as elasticity of muscle. The shorter the distance, the greater care and practice should be made in starting; the longer you have to sprint, the greater will be the necessity for working up the muscles. In practice, run with as slight clothing on as possible; buff is to be preferred. The action of the air on the skin keeps up a healthy flow of blood to the surface, and will do more towards a beneficial reduction of weight than any amount of sweatings, baths, or other appliances of the old school

Quarter And Half Mile Running

A quarter of a mile is, perhaps, next to the 300 yards, the most patronized of any. Assuming our trainee to be in robust health, the muscles should be gradually accustomed to the exercise by slow spins of half a mile each, two or three times a day, taking about from 3min. to 2min. 25sec., according to the individual, to do it. When the distance is accomplished with comparative ease, practice style and pace for about 300 yards to 350 yards to within about a week of the race, when the whole distance may be run, two or three times at top speed for 400 yards, slower the last 40. Ease up the practice in the last three days, merely working up pace for 100 yards or so. The same method of training will suit the half mile runner, with the exception of his spins being longer, and more attention paid to an equal pace of going. The quarter requires more speed than the half mile; consequently that point must be attended to. A steady, machine-like style of going pays best for the half mile runner.

One Mile Running And Upwards

In practicing for a mile race and upwards, a long, steady course of slow running must be gone through to get the limbs and the wind gradually accustomed to the work. As they improve, quicken your pace, and for mile running practice half a mile or so in about 2min. 20sec., until the wind becomes good; then lengthen the daily spins to three-quarters of a mile fast, and the last quarter slowly. Never do much work the last few days, but have a few fast spins of 300 yards or so, to keep the muscles in form. In longer distance training, the same steady practice must be followed, with this exception, that, instead of practicing pace, rather get the condition of wind and muscle up as high as practicable, and reserve your energies for the day of the race.

Hurdle Racing

The usual hurdle race distance is 120 yards, with 10 flights of hurdles 3ft. 6in. high and 10 yards apart. This gives a run of 15 yards at both ends. The quickest way of getting over them is by taking them in stride, or technically bucking them. If the ground is firm and level, this can be done, and three strides will take the jumper from hurdle to hurdle, the fourth taking him over. Should the ground be uneven, slippery or heavy, great care is required in bucking them. Touching the top bar will inevitably be followed by a fall or a stumble sufficient to put the jumper out of the race. In bucking, the spring is taken from one leg, and the alight comes on the other; so that the jump, instead of being an actual interruption of the regular strides, as happens when the spring and the alight come on the same leg, is merely an exaggerated stride. The advantage of bucking is apparent to anyone who has tried both systems under favorable circumstances, and who is strong enough to bear the strain which the high hurdles require. The lower the hurdles are, the greater is the superiority of bucking over jumping. To acquire the art of taking the hurdles in stride, practice over jumps about 2ft. 6in. high, at the proper distance apart, until the style is learnt.

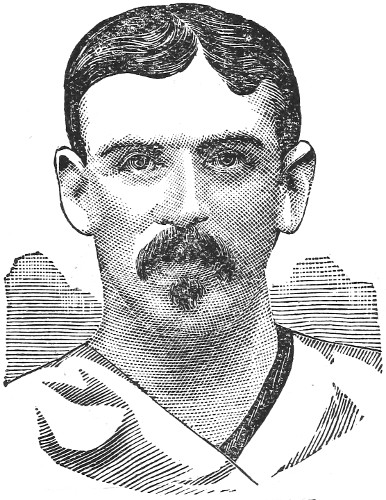

HARRY VAUGHAN, The Famous English Long-distance Walker

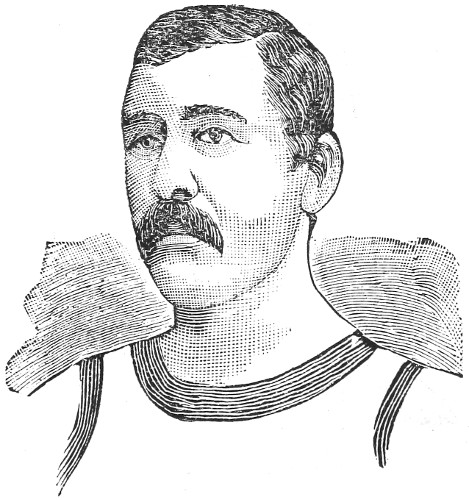

JOHN HUGHES, First Winner O'Leary International Belt

DAN'L O'LEARY

Hints In, Before And After The Race

In sprinting, a good start is of such importance that we would suggest a careful practice in it. It is a curious fact that a novice will invariably start with one foot a yard or so behind the other, either with the body bent down low, or with the body erect, and swinging the arms as if they were the means of propulsion about to be trusted to. In the former case, he runs one yard more than his distance, in the latter he exhausts and unsteadies himself. Start with both feet within six inches of one another, the weight of the body resting on that foot which is farthest from the scratch, and the toe on the side nearest the goal, just touching the ground, and ready to take the first step over the mark; the body must be kept well up, so that the first spring is taken steadily and in a straight line. As this method is the quickest for getting off the mark, it will apply to every description of pedestrianism.

Before any contest, when you are stripped, take a trot to get the limbs into order and keep them warm; the muscles will be less likely to get strained if well heated beforehand. In running with a chicken-hearted man, race at him, and, if you feel done, fancy that he feels worse. Run as straight to the goal as possible; it is the nearest way home, and therefore the quickest. The arms should be kept well up, and moved in the direction of the course, and not swung across the body. Any scrambling in the race is fatal to a good walker; the motion of his legs should be mechanical. In walking races, if a stitch bothers you, keep well on, and try and forget it; it will never last long if you are in good condition. In a race with heats, after a heat lie down on your back, and keep the legs raised up, in order that the blood forced into the extremities by the exercise may be assisted by its own gravity to return to the trunk. Rest is the best cure for a strain, and is much assisted by cold water application. In a strain of the internal organs, their complexity renders repair a more difficult operation, as they do not allow of repose; recourse should therefore be had to a physician.

Running on the toes on a path is to be recommended, as enabling a longer stride to be taken, and giving an easier motion to the body, and less jar at each step. In heavy ground, however, it is of little use, as the sinking of the toe in the soil interferes with the spring, and necessitates a larger surface of the foot to get a purchase for the next stride.

Never in practice run with many clothes on; if the weather is cold, clothe in proportion. The action of the air on the skin increases its healthy vigor. A piece of cork is often held in each hand to grasp while running. In a long distance race, rinsing the mouth out with warm tea with a little brandy in it, and munching a crust, will often take away any dryness of throat. Never commence fast sprinting in practice unless the muscles are thoroughly warm. Strains would seldom happen if this was attended to. Fruit fresh picked is not to be discarded. A small quantity, when ripe, will often give tone to the stomach and cool the blood. Of dried fruits, figs are supposed to be the most serviceable.

Training Practice And Fair Walking

Walking is the most useful and at the same time most abused branch of athletic sports; not so much from the fault of the pedestrians as from the inability or want of courage of the judge or referee to stop the man who, in his eagerness for fame or determination to gain money anyhow, may trespass upon fair walking, and run. Walking is a succession of steps, not leaps, and with one foot always on the ground. The term “fair toe and heel” was meant to infer that, as the foot of the back leg left the ground, and before the toes had been lifted, the heel of the foremost-foot should be on the ground. Even this apparently simple rule is broken almost daily, in consequence of the pedestrian performing with a bent and loose knee, in which case the swing of his whole frame when going at any pace will invariably bring both feet off the ground at the same time; and although he is going heel and toe, he is not taking the required succession of steps, but is infringing the great and principal one, of one foot being continually on the ground. The same fault will be brought on by the pedestrian leaning forward with his body, and thereby leaning his weight on the front foot, which, when any great pace is intended, or the performer begins to be fatigued, first merges into a very short stride, and then into a most undignified trot. There is no finer sight among the long catalogue of athletic sports, more exhilarating and amusing to the true sportsman, than to see a walking-match carried out to the strict letter of the meaning, each moving with the grandest action of which the human frame is capable, at a pace which the feeble frame and mind is totally unable to comprehend, and must be witnessed to be believed. To be a good and fair walker, according to the recognized rule among the modern school, the attitude should be upright, or nearly so, with the shoulders well back, and the arms, when in motion, held well up in a bent position, and at every stride swing with the movement of the legs, well across the chest, which should be well thrown out. The loins should be slack, to give plenty of freedom to the hips, and the leg perfectly straight, thrown out from the hip boldly, directly in front of the body, and allowed to reach the ground with the heel being decidedly the first portion of the foot to meet it. The movement of the arms, as above directed, will keep the balance of the body, and bring the other leg from the ground, when, the same conduct being pursued, the tyro will have accomplished the principal and most difficult portion of his rudiments. This will in a very short time become natural to him, and the difficulty will be the infringement of the correct manner. The novice having learned how to walk, and being matched, requires training, which must be under the same rules as have been laid down previously, with the difference, however, that his sweats must be taken at his best walking-pace, the trot by all means being totally barred. A continued perseverance in the practice of this rule will enable the pedestrian to persevere, notwithstanding all the shin-aches, stitches, and other pains attendant on the proper training for a walking-match, and which every man must undergo before he can be considered worthy of being looked upon as a fast and fair walker. The tyro must not be discouraged with his first feeble and uncertain attempts if they should not come up to his crude anticipations, but bear in mind that, although the accomplished pedestrian goes through his apportioned task with great apparent ease, he has gone through the rudiments, and that nothing but great practice has enabled him to perform the apparent impossibilities which are successfully overcome almost daily. Therefore the young walker must take for his motto “Perseverance,” and act up to the same by continued practice. The man training for a match should walk some portion of his distance, if weather permits, daily, in his walking-dress, which should consist of a light elastic shirt, short drawers, and light Oxford ties. On starting, he must go off at his very best pace, and continue it for at least three hundred yards or a quarter of a mile, by which time he will have begun to blow very freely, and then, getting into a good, long, regular stride, his principal aim must be to keep his legs well in advance of his body.

The rule of getting away fast in trials should be invariably carried out; it prepares the man for a sharp tussle with his opponent for the lead, and will hinder him being taken off his legs in the match. When tired he can also ease his exertions; but if he is in the habit of going off at a steady gait, in the generality of instances he is virtually defeated in a match before he has commenced racing. Moreover, he must, when undergoing distress from the pace he has been doing, never by any chance cease his resolute and ding-dong action; for distress, if once given way to by easing, will of course leave the sufferer, but at the same time all speed has also departed, and not for a short space of time either, but sufficiently long for the gamer man, who would not succumb to the inevitable result of continued severe exertion, to obtain such an advantage as would be irrecoverable, as well as to conquer the aches and pains which invariably leave the well-trained pedestrian when the circulation and respiration become equalized—“second wind” it is better known by. After this happy and enviable stage of affairs has been reached the work becomes mechanical, and the pedestrian from time to time is enabled to put on spurts and dashed that would astonish himself at any other time when not up to thorough concert pitch. The recovery from these electrifying dashes is almost instantaneous, and the pedestrian keeps on his satisfactory career until sheer fatigue gradually diminishes his speed, although none of the previous aches and pains are present. The trainer must not forget the previously-mentioned rule of stopping the man when good time is not the result of his best and hardest exertions, as that bad time proves unerringly that something must be amiss which requires looking to thoroughly. As well might the engineer of a locomotive, on finding out that some of the internal works of his engine were out of gear, put on all his steam, and then wonder at the machinery being out of order at a future time of trial.

One word more. Let the man continually bear in mind that “it is the pace that kills,” and that slow walking never made a fast race or fast man; let him practice at his best pace, which will daily improve. The commencement of fast work will most likely bring on pain of the shins, which will be sore after the exertion has been discontinued, as well as other portions of the frame being in the same predicament. Hand-rubbing with a stimulating embrocation before a good fire will in most instances be all that is required; but if obstinate, a hot bath will insure the removal of all the obstinate twitches, etc. The shoes for match-walking should be of the lightest description commensurate with strength for the distance required. They should be of sufficient width and length to give the muscles and tendons of the foot full play, without being in the slightest degree cramped. They should be laced up the front, and care taken that the lace is sound and new. So much importance is attached to this, that stout wax-ends are now invariably in use. Some advocate the use of boots; but, although stated to be useful if there is any weakness of the ankle—a pedestrian with weak ankles!—is there no cold water?—the heat generated by them would certainly counterbalance the supposed benefit; and there is the difference in the weight, which would tell at the finish of a long match.

End of Practical Athletics (Walking And Running) by Ed James